Anatomy

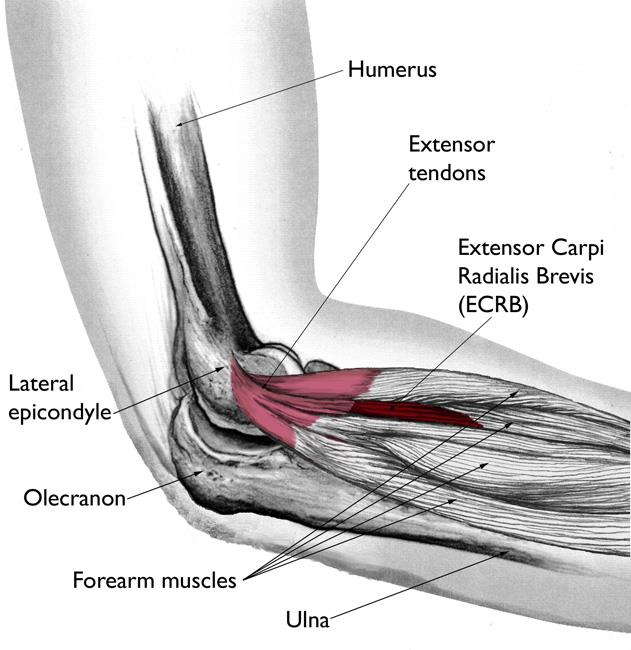

Your elbow joint is a joint made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus) and the two bones in your forearm (radius and ulna). There are bony bumps at the bottom of the humerus called epicondyles, where several muscles of the forearm begin their course. The bony bump on the outside (lateral side) of the elbow is called the lateral epicondyle.

Muscles, ligaments, and tendons hold the elbow joint together.

Lateral epicondylitis, or tennis elbow, involves the muscles and tendons of your forearm that are responsible for the extension of your wrist and fingers. Your forearm muscles extend your wrist and fingers. Your forearm tendons — often called extensors — attach the muscles to bone. The tendon usually involved in tennis elbow is called the Extensor Carpi Radialis Brevis (ECRB).

Cause

Overuse

Recent studies show that tennis elbow is often due to damage to a specific forearm muscle. The extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) muscle helps stabilize the wrist when the elbow is straight. This occurs during a tennis groundstroke, for example. When the ECRB is weakened from overuse, microscopic tears form in the tendon where it attaches to the lateral epicondyle. This leads to inflammation and pain.

The ECRB may also be at increased risk for damage because of its position. As the elbow bends and straightens, the muscle rubs against bony bumps. This can cause gradual wear and tear of the muscle over time.

Activities

Athletes are not the only people who get tennis elbow. Many people with tennis elbow participate in work or recreational activities that require repetitive and vigorous use of the forearm muscle or repetitive extension of the wrist and hand.

Painters, plumbers, and carpenters are particularly prone to developing tennis elbow. Studies have shown that auto workers, cooks, and even butchers get tennis elbow more often than the rest of the population. It is thought that the repetition and weight lifting required in these occupations leads to injury.

Age

Most people who get tennis elbow are between the ages of 30 and 50, although anyone can get tennis elbow if they have the risk factors. In racquet sports like tennis, improper stroke technique and improper equipment may be risk factors.

Unknown

Lateral epicondylitis can occur without any recognized repetitive injury. This occurrence is called “idiopathic” or of an unknown cause.

Symptoms

The symptoms of tennis elbow develop gradually. In most cases, the pain begins as mild and slowly worsens over weeks and months. There is usually no specific injury associated with the start of symptoms.

Common signs and symptoms of tennis elbow include:

- Pain or burning on the outer part of your elbow

- Weak grip strength

- Sometimes, pain at night

The symptoms are often worsened with forearm activity, such as holding a racquet, turning a wrench, or shaking hands. Your dominant arm is most often affected; however, both arms can be affected.

Doctor Examination

Your doctor will consider many factors in making a diagnosis. These include how your symptoms developed, any occupational risk factors, and recreational sports participation.

Your doctor will talk to you about what activities cause symptoms and where on your arm the symptoms occur. Be sure to tell your doctor if you have ever injured your elbow. If you have a history of rheumatoid arthritis or nerve disease, tell your doctor.

During the examination, your doctor will use a variety of tests to pinpoint the diagnosis. For example, your doctor may ask you to try to straighten your wrist and fingers against resistance with your arm fully straight to see if this causes pain. If the tests are positive, it tells your doctor that those muscles may not be healthy.

Tests

Your doctor may recommend additional tests to rule out other causes of your problem.

- X-rays. These tests provide clear images of dense structures, such as bone. They may be taken to rule out arthritis of the elbow.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. MRI provides images of the body’s soft tissues, including muscles and tendons. An MRI scan may be ordered to determine the extent of damage in the tendon or to rule out other injuries. If your doctor thinks your symptoms might be related to a neck problem, he or she may order an MRI scan of the neck to see if you have a herniated disk or arthritic changes in your neck. Both of these conditions can produce arm pain.

- Electromyography (EMG). Your doctor may order an EMG to rule out nerve compression. Many nerves travel around the elbow, and the symptoms of nerve compression are similar to those of tennis elbow.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Approximately 80% to 95% of patients have success with nonsurgical treatment.

Rest. The first step toward recovery is to give your arm proper rest. This means that you will have to stop or decrease participation in sports, heavy work activities, and other activities that cause painful symptoms for several weeks.

Medications. Acetaminophen or anti-inflammatory medications (such as ibuprofen) may be taken to help reduce pain and swelling

Physical therapy. Specific exercises are helpful for strengthening the muscles of the forearm. Your therapist may also perform ultrasound, ice massage, or muscle-stimulation techniques to improve muscle healing.

Brace. Using a brace centered over the back of your forearm may also help relieve symptoms of tennis elbow. This can reduce symptoms by resting the muscles and tendons.

Steroid injections. Steroids, such as cortisone, are very effective anti-inflammatory medicines. Your doctor may decide to inject the painful area around your lateral epicondyle with a steroid to relieve your symptoms.

Platelet-rich plasma. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a biological treatment designed to improve the biologic environment of the tissue. This involves obtaining a small sample of blood from the arm and centrifuging it (spinning it) to obtain platelets from the solution. Platelets are known for their high concentration of growth factors, which can be injected into the affected area. While some studies about the effectiveness of PRP have been inconclusive, others have shown promising results.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy. Shock wave therapy sends sound waves to the elbow. These sound waves create “microtrauma” that promotes the body’s natural healing processes. Shock wave therapy is considered experimental by many doctors, but some sources show it can be effective.

Equipment check. If you participate in a racquet sport, your doctor may encourage you to have your equipment checked for proper fit. Stiffer racquets and looser-strung racquets often can reduce the stress on the forearm, which means that the forearm muscles do not have to work as hard. If you use an oversized racquet, changing to a smaller head may help prevent symptoms from recurring.

Surgical Treatment

If your symptoms do not respond after 6 to 12 months of nonsurgical treatments, your doctor may recommend surgery.

Most surgical procedures for tennis elbow involve removing diseased muscle and reattaching healthy muscle back to bone.

The right surgical approach for you will depend on a range of factors. These include the scope of your injury, your general health, and your personal needs. Talk with your doctor about the options. Discuss the results your doctor has had, and any risks associated with each procedure.

Open surgery. The most common approach to tennis elbow repair is open surgery. This involves making an incision over the elbow.

Open surgery is usually performed as an outpatient surgery. It rarely requires an overnight stay at the hospital.

Arthroscopic surgery. Tennis elbow can also be repaired using miniature instruments and small incisions. Like open surgery, this is a same-day or outpatient procedure.

Surgical risks. As with any surgery, there are risks with tennis elbow surgery. The most common things to consider include:

- Infection

- Nerve and blood vessel damage

- Possible prolonged rehabilitation

- Loss of strength

- Loss of flexibility

- The need for further surgery

Rehabilitation. Following surgery, your arm may be immobilized temporarily with a splint. About 1 week later, the sutures and splint are removed.

After the splint is removed, exercises are started to stretch the elbow and restore flexibility. Light, gradual strengthening exercises are started about 2 months after surgery.

Your doctor will tell you when you can return to athletic activity. This is usually 4 to 6 months after surgery. Tennis elbow surgery is considered successful in 80% to 90% of patients. However, it is not uncommon to see a loss of strength.